![]()

'Levi-Strauss says he was most influenced by Freud and Marx - and geology....' - Anthony Wilden, System and Structure: Essays in Communication and Exchange

While it’s not quite true that esoterism is opposed to hyperstitional practice, it remains the case that the esoteric at best awaits a hyperstitional carrier and at worst is actually inhibitive of hyperstitional propagation.

Need it be reiterated that hyperstition is to be located, not in the deliberately inaccessible territory of hermetic pondering, but in pulp? Far from being reducible to the popular, or worse still, the populist, pulp is essentially propagative. It lurks and spreads in the paradoxical spaces – dark but lurid, mass marketed but intensely intellectual - beyond the gaze of the media big Other and its ruthlessly imposed pop-ontology of ‘commonsense’. Such spaces are rare to the point of near extinction in the hyperbright, hypervisibile malls of contemporary postmodern entertainment culture, where everything is not only known but knowing.

Britain in the seventies, however, teemed with pulp. From New English Library paperbacks, to the last garish productions of Hammer studios, to the nascent market in video nasties, to children’s television, the combination of eastern-bloc-like cultural austerity, Glam, speed, the fag end of psychedelia and a still surviving rag-tag labyrinths of non-franchised book and magazine emporia were a fertile breeding and feeding ground for pulp production.

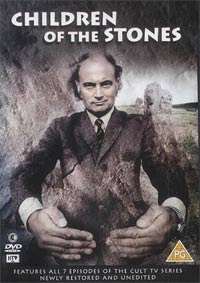

So, to children’s television, and HTV West’s 1977 production, Children of the Stones.

The thing that children who saw the serial when it was first broadcast are liable to retain most powerfully in their spinal cord body memory is the music: harrowing atonal chants reminiscent of Penderecki and Ligetti which made the looming close-ups of megaliths scream with millennia-old panic. Like the young viewers of Dr Who, the audience of Children of the Stones was infected by sounds far more disturbing and deranged than anything rock has ever come up with.

The serial was filmed in the parchingly hot drought summer of 1976 in Avebury, Wiltshire, which might have seemed a world away from the first flarings of punk in London. In fact, Children of the Stones goes alongside what is best in punk in its (literal) strato-analysis of the libidinal-material nature of power .

Children of the Stones is about Petros, the black hole vampire-god of disintensifaction and intensive death, whose hunger for star-energy is similarly diagrammed in Burroughs’ Nova Trilogy.

Children of the Stones belongs to a micro-genre connecting two British seventies’ obsessions, stone circles and outer space, that might be called megalithic astropunk. The other major work in this field is Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass swansong.

The serial opens by (presumably self-consciously) echoing Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Children of the Damned, Quatermass II, The Wicker Man and The Stepford Wives, inducting its two lead characters , astrophysicist Adam Brake and his son, Matthew, into a near-closed community of ‘happy’ people. One of the great services such fictions provided was to make its young viewers intensely suspicious both of ‘happiness’ as an emotional state and of those who proffer it as a libidinal-political goal.

In the case of Children of the Stones, the Grand Inquisitor Utilitarian-priest is Hendrick, the unctuous-charming Lord of the Manor. It is no surprise at all to learn that Hendrick, a semi-retired astrophysicist who has discovered a supernova, turns out also to be a white magician: a magus, as Adam describes him as the series comes to a close. Like many pulp master villains, Hendrick is not straightforwardly a malevolent monster, but a beamingly altruistic administrator of the pleasure principle, a manager of the hedonic calculus, even as he is an agent of (Burroughs) control. The price of such ‘happiness’ – a state of cored-out, cheery Pod people affectlessness – is sacrifice of all autonomy.

Are we being asked, then, to side with human consciousness against the alien unconscious? Isn’t, after all, freedom from the passions a Spinozist goal? Yes, but freedom from sad passions is not the end of the story if it is at the price of a ‘happy’ passivity, a blank-eyed disengagement from all Outsides, as all (your) energy is sucked up by the ultimate interiority, the time-space implosion of Nova.

Under such pressure, you become a stone.

You become petrified. (Even when you are happy.)

Children of the Stones is also self-consciously a mediation on mythic structure. The circle that encloses the village (called Milbury in the serial) is made up of 55 stones. There are fifty-three people living in the village before Adam and Matthew arrive. Hendrick doubles the Neolithic seer who bore witness to the death of the star with which the stone circle is aligned.

To be in the village is to assume a role in an aeonic structure. As Matthew observes at the very end of the last episode, Time is itself a kind of circle. Matthew and his father’s flight from the not quite closed circle is in its own way an integral part of the cybernetics of the Petros-machine as is the other villagers submission to it. Control needs something to control, no circuit can function without an Outside, no circle is ever completely closed.

Petros needs you.