![]()

'Hell is a city much like London' - Shelley

'Flesh is easy to shape.' - 'Clay Man', Swans

Step into Tate Britain at the moment and you find yourself in Anthony Caro's Hell. The Last Judgement is part of the sculptor's final, and surely most accomplished, phase of production.

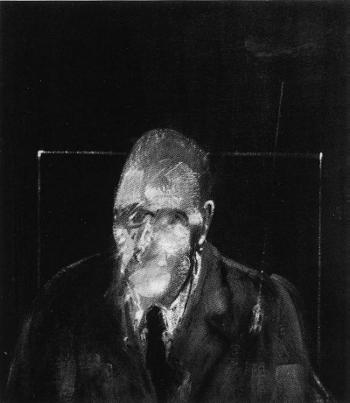

Caro's early work was figurative - but figurative in the way that Bacon's or Jack Kirby's was, textbook Deleuzian in its rendering of animal forms as lines of force and energy. In contrast with the smooth surfaces favoured by Henry Moore (with whom Caro had worked as an assistant), Caro's pieces were rough-hewn, asymmetrical; empirically distorted but faithful to the Real of the intensive bodies whose torsion they arrested in plaster and bronze.

Like Bacon's crouches (examples of which can be seen in the room devoted to Bacon, adjacent to where the Last Judgement is displayed), these pieces break through the screen of phenomenal difference to access the energy formations that find expression across animal and geological strata. They are diagrams, not organic representations: freezes without frames, since Caro eschewed plinths and and pedestals and placed his sculptures on the same level as that of their viewer, already anticipating the confusion of sculpture and architecture that late works like the Millbank Steps (produced specificially for the Tate) will explore.

Under the influence of Clement Greenberg, Caro abandoned figuration completely in the second and most celebrated phase of his career, arranging and garishly painting found objects such as girders. Although this is the work which made Caro's reputation, it now looks unengagingly canonic. These austere clean lines are the very stuff of which the postmodern is made: literally. You are reminded of the literal vacuity of the postmodern domestic and corporate spaces, which recoil in horror from the unruly zigzagging lines of the Gothic.

Despite the success of this work (or perhaps because of it), Caro was dissatisfied enough with it to move on, and his last phase of production - of which The Last Judgement is a stunning part - marks another turn, or rather a return: to Gothic abstract figuration.

The Last Judgement is an astonishingly welcome reminder that contemporary art can approach all the classical themes addressed by Dante, Shakespeare, Milton, Eliot, Bacon (all of whom it references) - without coming off worse. It has all the ambition and vastness which postmodern British art, with its demythologizing impulse towards tracing the empirical, its cult of vanitas (enslaved to two masters, celebrity and mortality) prides itself on having supposedly superceded.

This is the way, step inside

You don't contemplate The Last Judgement transcendently, you walk through it, which immanence gives a certain irony to the piece's title. Caro's message screams mutely out of every mouth gashed in plaster and iron: hell is not at the end of the road, not even round the corner, it is here, now. It will not be the judgement of a personal God that condemns you to infernal torment: your own animal vicissitudes put you there, now.

Abstraction and myth have always been strongly correlated. Abstract engineers don't 'create' any more than they trace (represent) - they discover and follow lines, cutting through the mire/ maya of what is presented to us so as to get to the stratificatory apparatuses and parasitic machines which produce the grim empirical charade we are invited to accomodate ourselves to in the name of 'realism'.

Each of the tableaux - crudely and fittingly boxed into caskets - capture an abstract mode and/ or intensive trap, sometimes identified as vice (sacrifice, greed and envy), at other times given names from epic drama or the Bible (Salome's Dance, The Furies, Charon) , or else simply given locational descriptions (Tribunal, Posion Chamber).

Time and again, wandering through the abstract atrocity exhibition, I am reminded of Mary Shelley's phrase 'workshop of filthy creation'. Caro's anguished abstractions, rust coloured and malformed out of clay and iron, cry out the Gnostic wisdom that we are ourselves the offcut slurry of a demented demiurge whose workshop of fithy creation this is.

Caro's waste land assemblages are Geurnica and Ernst's industrial jungles brought to still life: modernism redux. And, as Kurtz's bookshelf in Coppola's film makes clear, the real theme of modernism's revisited primitivism is always ---- apocalypse now.

If you approach from the front of the gallery, you enter through the ominous stockade-section of the bell tower (if the intended allusion here is Hemigway, I couldn't but be reminded, too, of the fated final scenes of Hitchcock's Vertigo). You are then faced with the door of Death, whose position here again suggests a Gnostic insight: identification with the organs is life is death.

But the casket whose grimly stolid contents ingrained itself most powerfully into my nervous system was 'Shades of Night'. Here hunched plaster sack-shaped figures with rudimentary Giacometti/ Tanguy heads and fixed halloween mask features stare inscrutably like Hellraiser scarcrows scarred out of geological residue. As ever, the real Gothic dread does not lie in the thought that these inanimate monstrosities might be alive (although Caro has the art of doing just enough to suggest that whatever quasi-anthropomorphic forms we fancy we see might only be accidental features of found objects) but quite the reverse. You see yourself diagrammed in these unhappy images of torturers tortured: I too am nothing but animated matter, the silent screaming product of a process without final purpose or deliberated intent.

Posted by mark k-p at February 21, 2005 12:53 AM